Vertigo

Alexandra Lawson Gallery, Toowoomba, 27 October - 12 December 2017

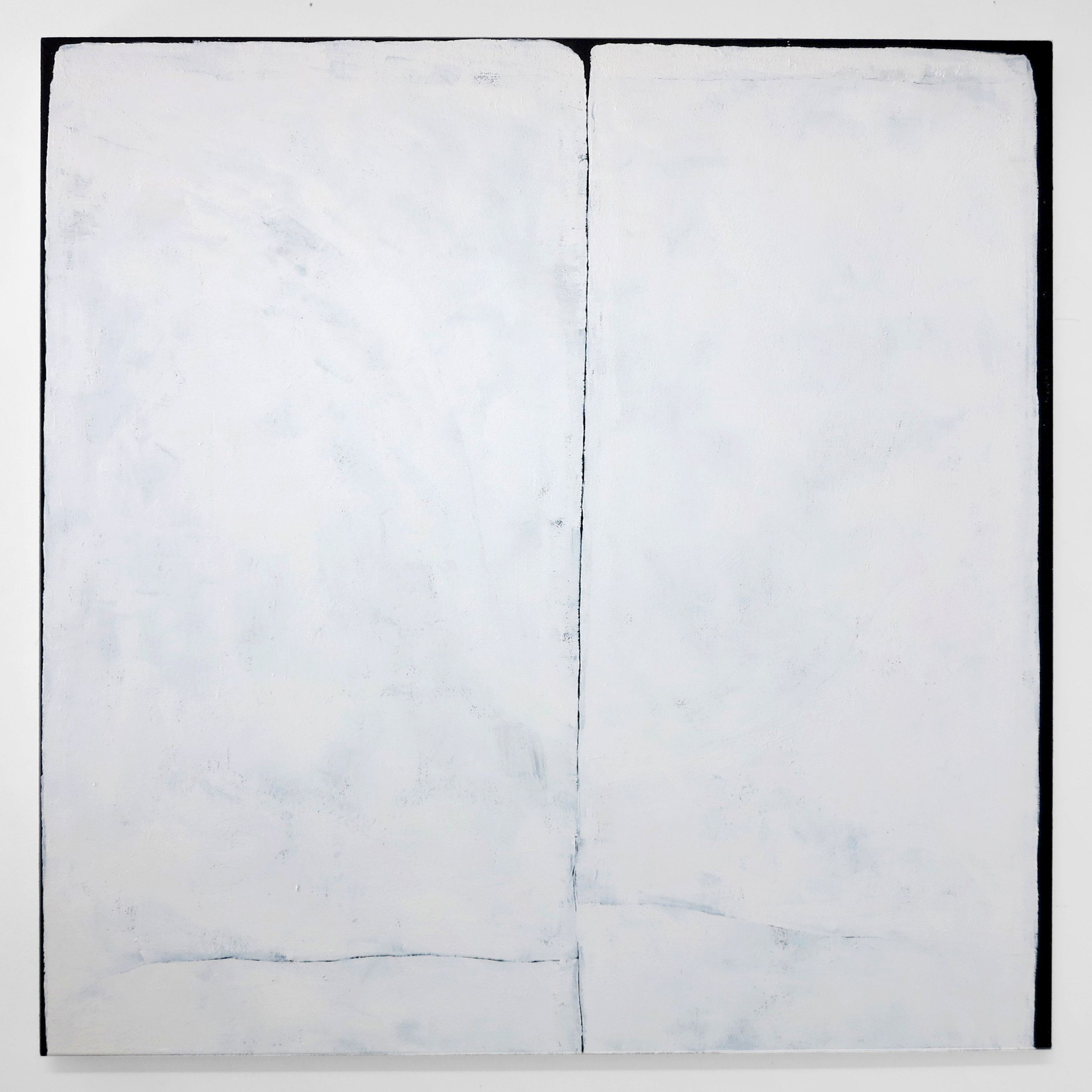

Install view, Alexandra Lawson Gallery

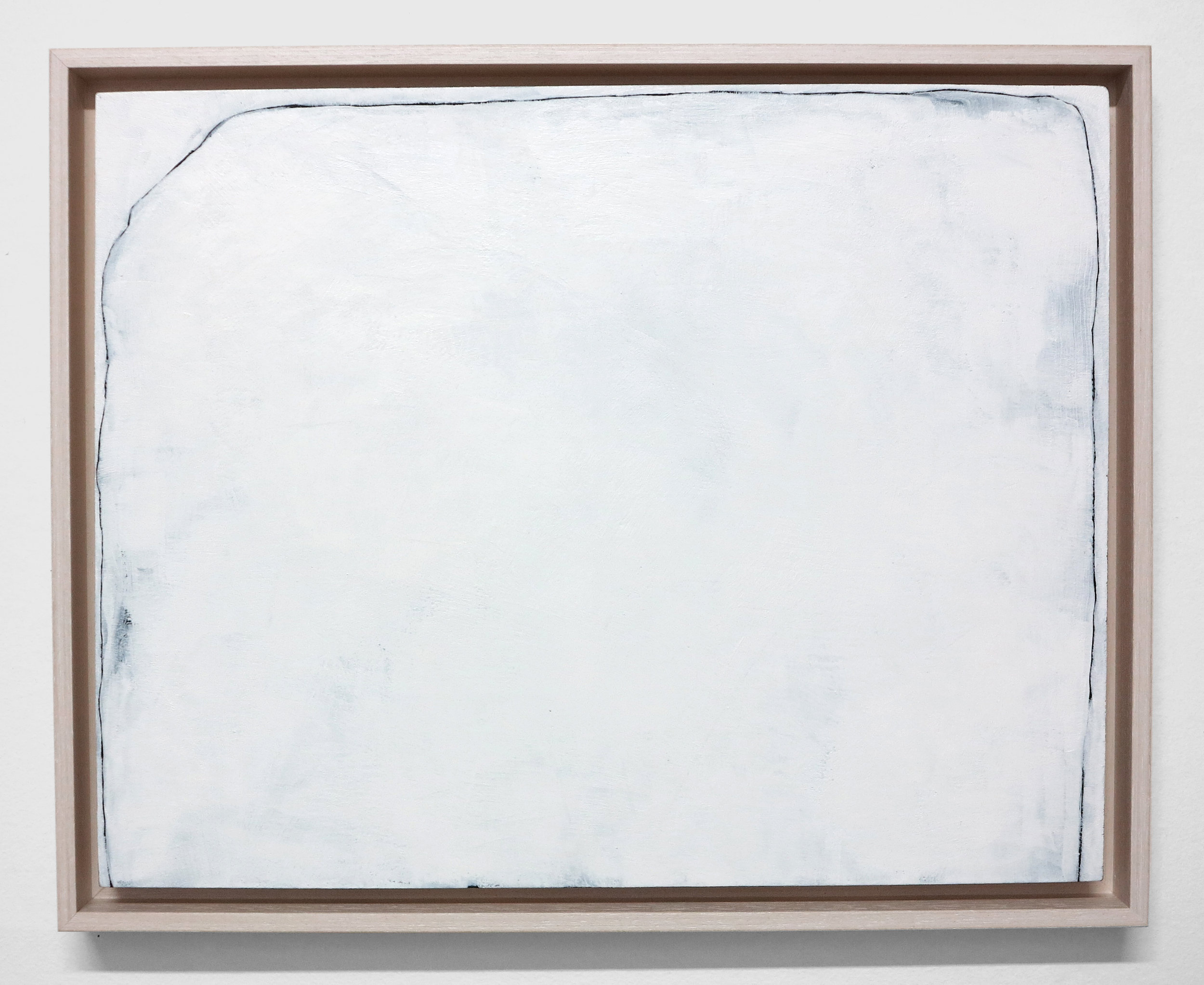

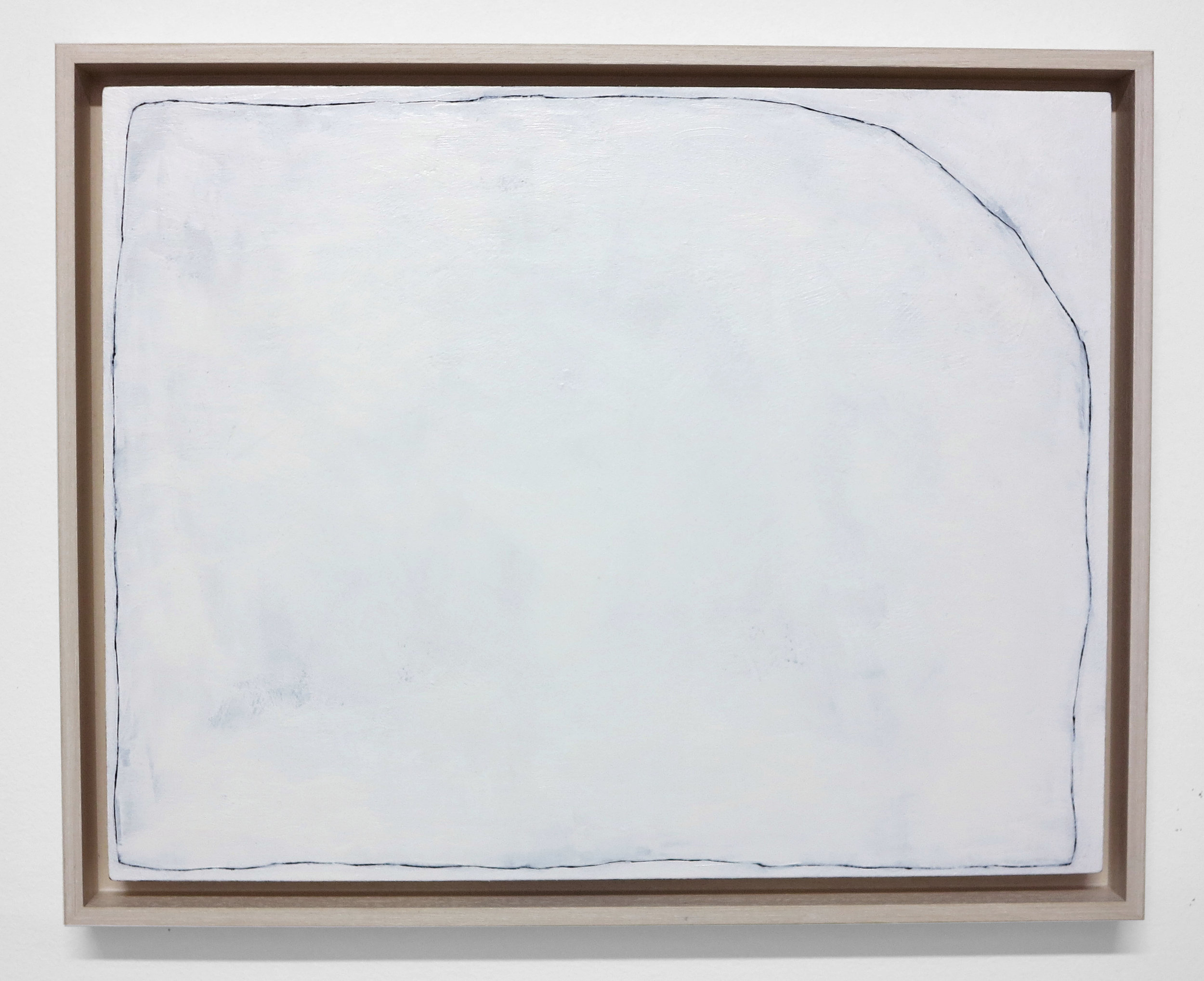

Line Drawing I, 2017, acrylic on board framed, 38.5 x 30.5cm

I look up from the base of a gorge in Western Australia. The ground feels unstable under my feet. I am overcome by the landscape that surrounds me. Personal, social, political, violent histories are embedded here. I am aware that these histories exist, but I do not know them, maybe I cannot really know them. Back home in Parramatta the landscape is different but still carries these histories. The feeling is the same: Vertigo. Unsettled, but at home.

Exhibition essay by Naomi Riddle

On Vertigo

‘I wanted the solid weight of history in brick and stone all around me and beneath my feet, holding me steady…The colony had no depth by comparison, nothing to keep you from spinning off into the wilderness.’

Jennifer Livett, Wild Island (2016)

1.

In the opening scene of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), we see the police detective John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson clambering up a flimsy ladder before racing over a rooftop. Hitchcock’s trademark strings tremble and thrash as Scottie struggles to catch up to an escaping criminal. The lights of San Francisco Bay wink in the background.

The assailant makes a leap between two buildings with ease, but Scottie tumbles, sliding down the slate tiles, barely hanging on, his fingertips wrapped around the edge of a rusty gutter.

He looks down.

The several-storey drop seems to fall away into a never-ending chasm; his grip on the gutter starts to give way. The edges of the buildings loom large in Scottie’s wobbling vision and the screen image itself is magnified, almost distorted, before fading to black.

Hitchcock’s opening sequence is one of the first times the ‘dolly zoom’ would be used in film. But from that moment on it garnered a new name – it would now simply be known as: ‘the Vertigo effect.’

2.

‘Vertigo’ is a Middle English word, a combination of the Latin vertigo – ‘to whirl’ and vertere meaning ‘to turn’. And the physical experience of vertigo is most often depicted as a spiraling circle, or a whirlpool turning around on itself. There’s the dizziness, the nausea, a feeling of collapse, but there’s also a tug, a loosening around the stomach. It’s a type of pull that sees you drawn to rather than repelled by the edge of a cliff face, or a guardrail, or a window. In experiencing vertigo, we find ourselves giving over: we cede control to the void.

3.

Hayley Megan French’s understanding of vertigo does not come from peering over a ledge at a great height. Instead, it comes from the act of looking up, of losing the coherent line of the horizon. The paintings in this exhibition reference a moment in Karijini National Park, Western Australia, when the high-lines of gorges and canyons suddenly crowded over, causing French’s balance to turn. The paintings themselves cause a similar feeling of disorientation in the viewer: perspective becomes unclear, as the marks on the canvas appear to be both a bird’s eye view of the landscape and the view from the ground.

4.

There is a moment in Shirley Hazzard’s novel The Transit of Venus (1980), where the protagonist Caroline Bell recollects her Australian childhood. She recalls the history teachers that told her about Australian explorers, of men who set out with heads full of hope, never to return: ‘journeys without revelation or encounter endured by fleshless men whose portraits already gloomed, beforehand, with a wasted, unlucky look – the eyes fiercely shining form sockets that were already bone.’[i]

It is said that many of these explorers did not just experience dehydration, hypothermia or starvation. Many found themselves overcome with a peculiar type of light-headedness – the loss of balance of those who had found themselves in an upside-down world, far away from their Empirical centre.

David Crouch writes of an ‘uncomfortable state of ungroundedness’, a vertigo-ridden condition that is linked to the legacy of British colonialism in Australia: ‘the ‘uncanny’ position of perpetually unsettled settlement.’[ii] In connecting the Australian landscape to the sensation of vertigo, French is gesturing towards this particular form of colonial anxiety. Here earth and country deny comprehension; they refuse to be claimed.

5.

The filmmaker Chris Marker when writing about Hitchcock’s Vertigo, argues that the film is not just about space and falling, but ‘yet another kind of vertigo, much more difficult to represent – the vertigo of time.’[iii] And French is similarly working with an unsteadiness that is not just spatial but temporal as well. In reusing old canvases and painting over previous works, French adds layer upon layer, suspending moments of time through a gentle process of accretion: she maps out a landscape; she erases another. But previous brushstrokes, or a splash of colour, still find their way onto the final canvas. Just as Scottie’s vision blurs when he looks down to the distant footpath below, so too do French’s paintings shift and tremble underneath one another. It is, as the poet John Keats would have described, a kind of ‘negative capability’ – a moment where we are ‘capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.’[iv] To experience negative capability is undoubtedly to also experience a moment of vertigo, but it is a moment that for all its giddiness still allows for a flash of calm in the pervading disquiet.

Naomi Riddle

[i] Shirley Hazzard, The Transit of Venus, (London: Virago Press, 2004 [1980]), p. 32

[ii] David Crouch, ‘Writing of Australian Dwelling: Animate houses and anxious ground’, Journal of Australian Studies, 27.80, (2003), pp. 44, 51

[iii] Chris Marker, ‘A free replay (notes on Vertigo)’, (1994): https://chrismarker.org/chris-marker/a-free-replay-notes-on-vertigo/

[iv] John Keats, ‘Letter’ (1817), quoted in Mary Ruefle, Madness, Rack and Honey, (Seattle and New York: Wave Books, 2012), p. 120

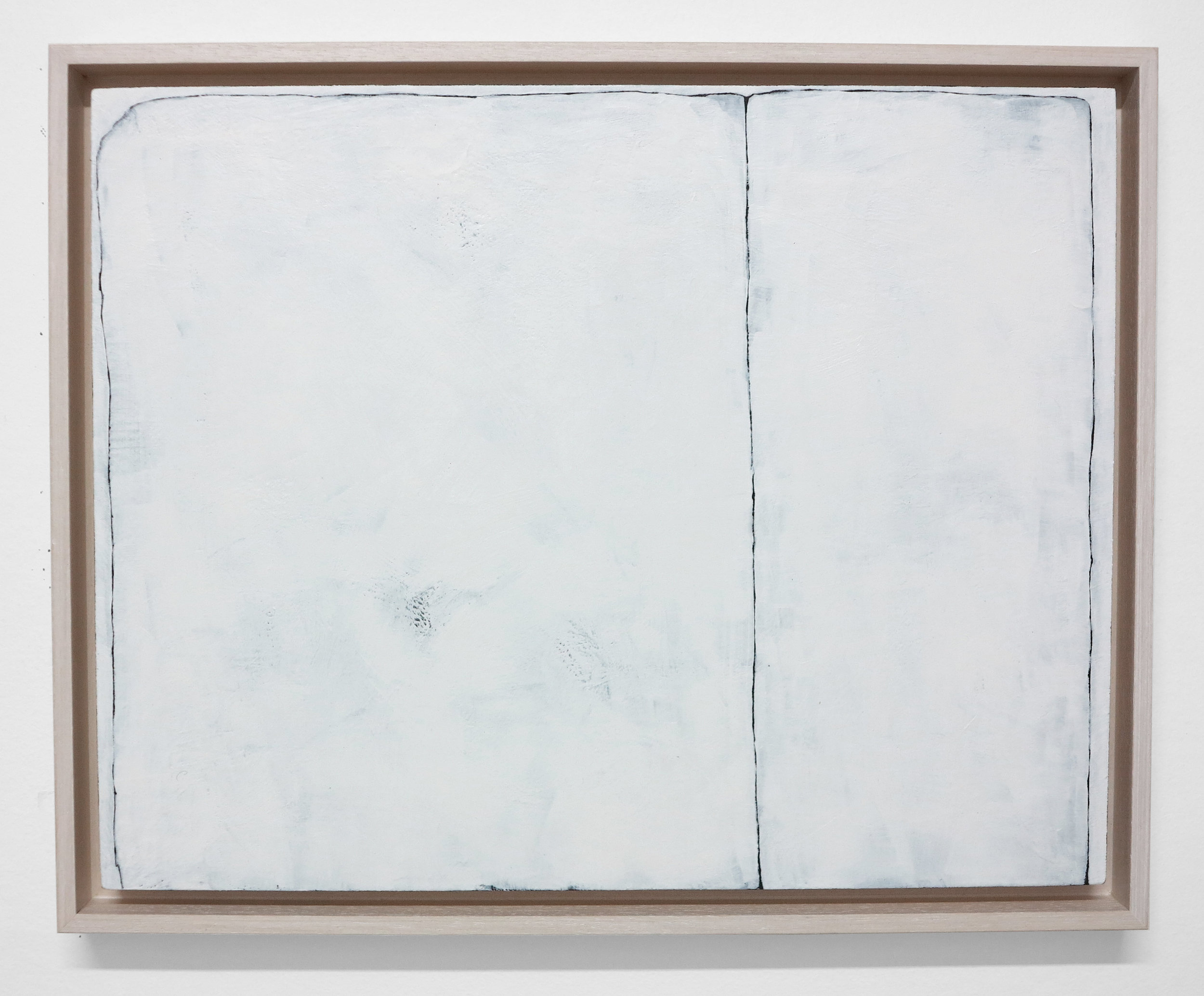

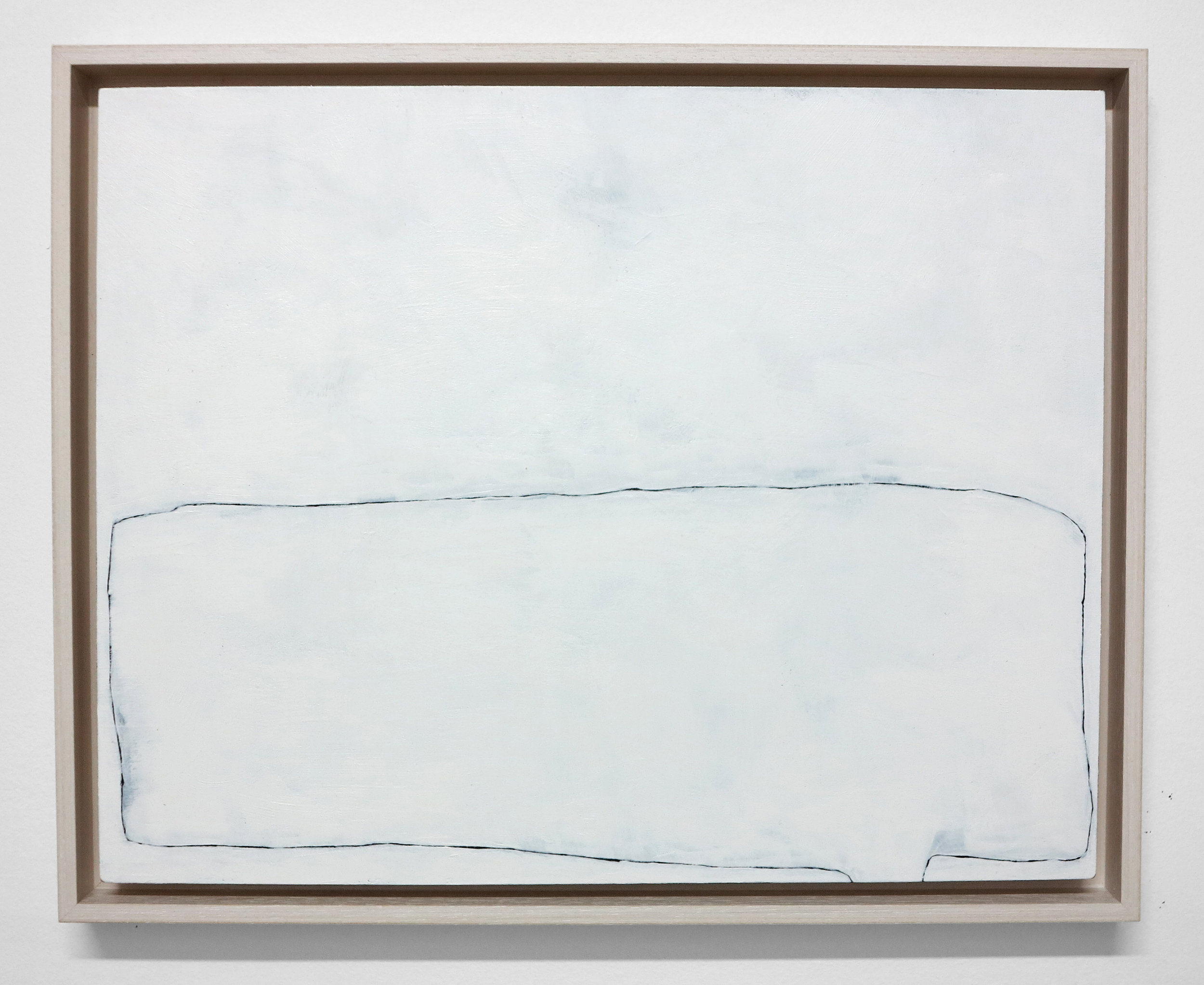

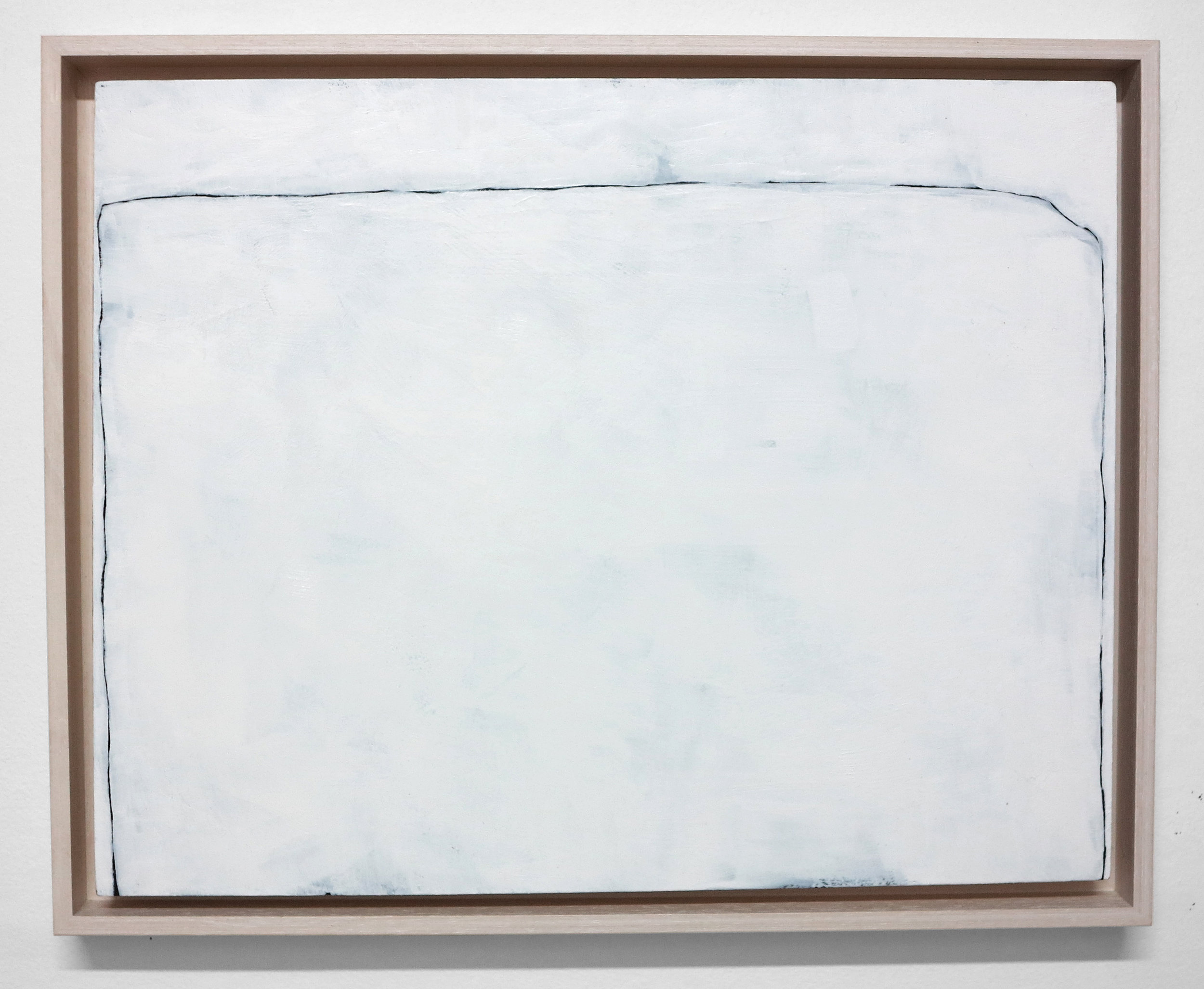

Install view, Alexandra Lawson Gallery

Install view, Alexandra Lawson Gallery

Install view, Alexandra Lawson Gallery